Anastasia Walker on selfies, seasons, and swimming in the ocean 🤳🍃🌊

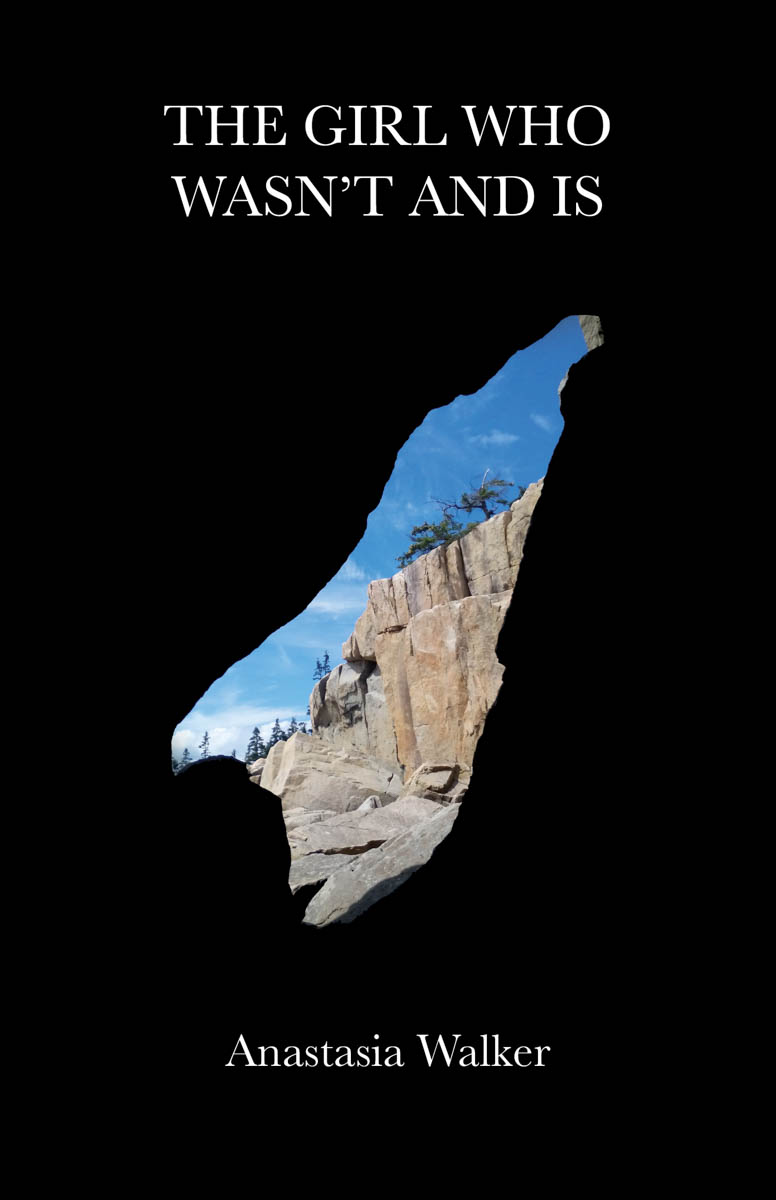

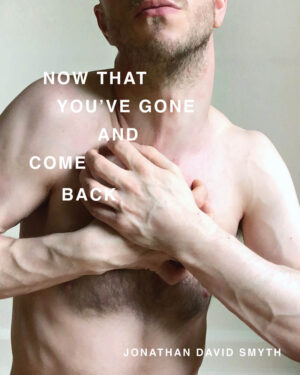

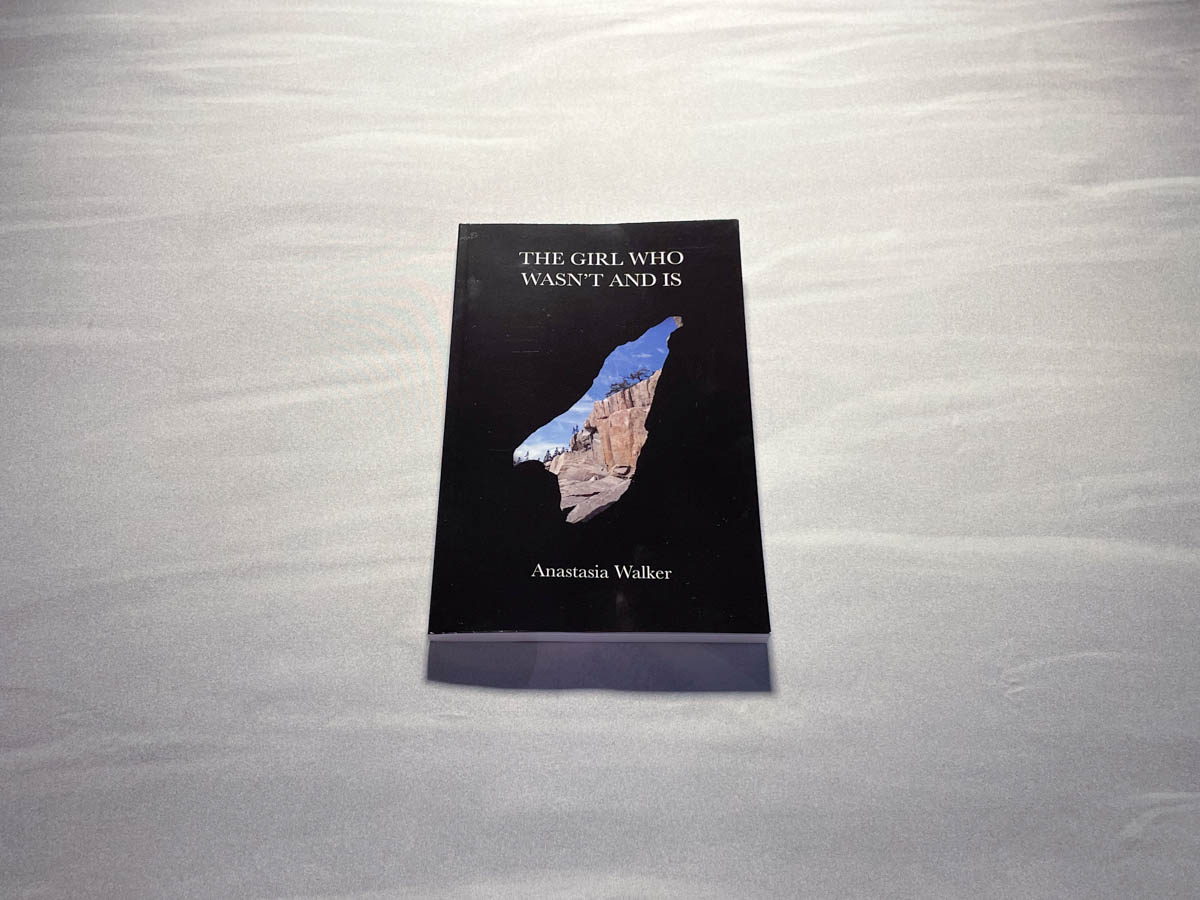

I was eager to talk with the gracious and witty Anastasia Walker, trans writer and photographer, to learn more about her transition and the inspiration behind her new book, The Girl Who Wasn’t and Is.

SK: Let’s start with the essay that concludes your book because reading it brought everything together for me. You express a longstanding distrust of cameras, yet you thrive in the medium of photography. How does your reappropriation of the medium help shift viewers’ perspectives?

AW: The selfie that essay starts with is a good place to begin. I took it when I was still finding myself and getting comfortable being out. Selfies, as part of the genre of portrait photography, and paintings before that, are informed by cis-normative conventions. A “good” selfie shows you looking and acting in ways that are typical for cis members of your gender. For women, it means meeting standards of beauty set by the movie and fashion industries. Becoming aware of these expectations, I was confronted with questions. Should I try to summon the smile that my friend in the essay chastised me about? Did performing all those expectations feel authentic? In that moment, it didn’t. And I liked that selfie because I was appropriating the genre to express my truth.

SK: You also use photography throughout The Girl Who Wasn’t and Is by pairing photos with poems. What are some of your favorite examples?

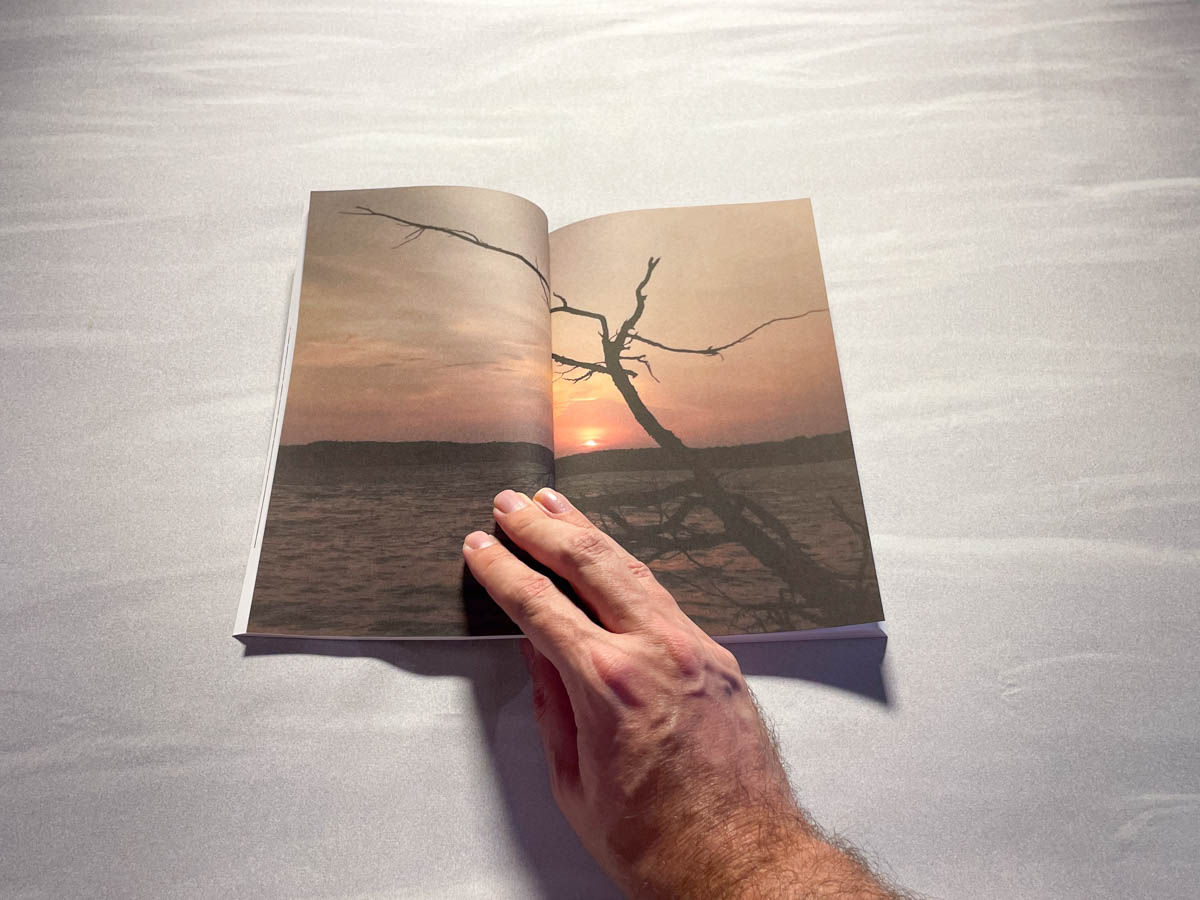

AW: I really like the pairings for “Seminality” and “November’s Child.” The first is about the burden of gender placed on all of us from the get-go. The OB peeked between my legs when I was born in 1964, assigned me male, and an entire future of expectations was activated. “November’s Child” shows a trans child of three or four, the age I first became self-aware, knowing there’s something wrong with that assignment. The accompanying photos show a crocus and dead autumn leaves on the pavement. In the latter image, you have a couple of freshly fallen leaves along with the imprints left by leaves that fell earlier in the season, which captures the ripening and dying that happens in autumn as a sort of time-lapse. Together, these two photos communicate this common experience of trans folks: the premature loss of innocence, like going from the April to the November of our lives in just a few years.

SK: I was struck by how you juxtapose the darkness of some of the poems with the brightness of the accompanying images.

AW: Yes, I used that to illustrate how violence plays out in our lives. The photo paired with the poem “For Muhlaysia,” for example, highlights how violence against trans folks too often happens out in the open. Muhlaysia Booker was assaulted in a parking lot in the middle of the day and beaten within an inch of her life. By contrast, the photo accompanying “Medusa” points to a type of violence invisible to cis people. I took it on a point of land near where I grew up in Maine. It was a very bright sunshiny day; I walked down to the water’s edge during low tide and found this small gorge with the waves surging violently into it. I paired that photo with the poem because it suggested the rape of Medusa by Poseidon, a metaphor for the onset of puberty. Puberty isn’t easy for most people, but for trans folks it can be really hard and was especially difficult before there were puberty blockers. What to cis people was a challenging but normal process of maturation could feel to us like a violation of who we knew ourselves to be, a rape that wounded us forever.

SK: At times, you identify your own body with nature, as in “The marvel of gently rolling plains of fat / The miracle of breasts.” Can you share more about coming to terms with yourself and identifying with nature?

AW: That relationship dates to my childhood. I explore its origins in “The Girl with Eyes of the Sea.” Like the girl in the poem, I couldn’t see myself, the trans girl I knew I was, in my community, in books, or on TV. I had no role models. I didn’t even have a word for what I was until I was a teenager, and it quickly became clear that if I openly asserted who I was, it would go very badly. I didn’t have to make that assertion in the natural world because nature didn’t judge me. I could go out into it and just be. I also found myself in that world in a way. My relationship with the Maine coast of my childhood was similar to how the poet Joy Ladin characterizes her relationship with God. Her god is a stern figure that doesn’t actively show love or otherwise reach out but is what remains when nothing else is left. Her god is simply always there.

SK: Is there a particular part of nature you feel most connected to?

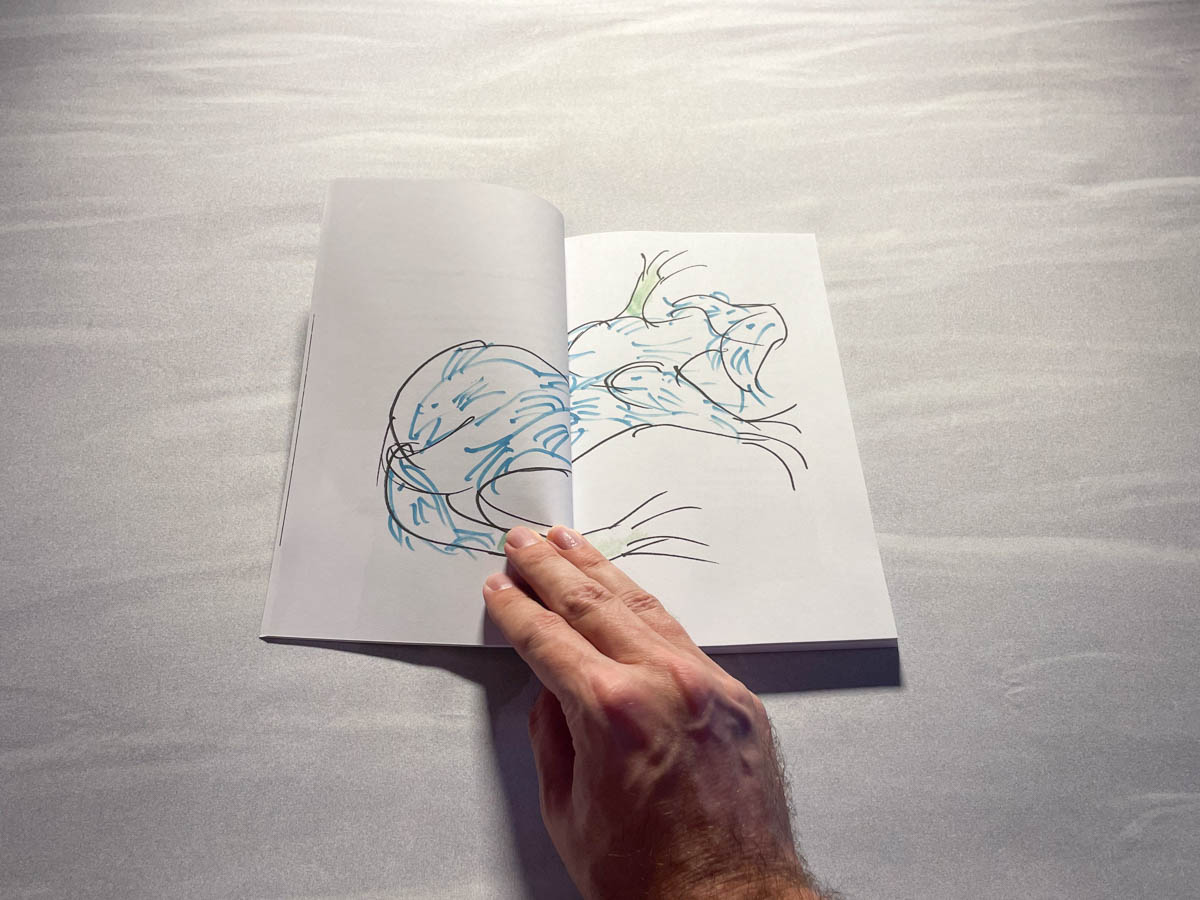

AW: Probably the ocean.I remember a fantasy I had as a kid swimming off our beach. At mid-tide, I would sometimes go out and swim through the seaweed and dive down from time to time. I learned early on to open my eyes underwater. Everything’s blurry and bright, kind of magical, and I would imagine myself as a seal in my jeweled home. I also have a sympathetic identification with seabound spirits like nereids. Thus the drawing I paired with “The Girl with Eyes of the Sea”—she “saw her face only / In the shimmering moon on the slumbering bay.” Ultimately, perhaps, the possibility for change, for a kind of fluidity, is why I love the water. The way the light is always sliding, it’s sort of chameleonic or amorphous, unlike the solidity of land and the position you’ve been assigned there. Things seem more dynamic in the water; evolution and difference seem possible. I don’t have to be what they’re telling me I am on land.

SK: Many of your poems deal with the physical and sexual violence perpetrated on trans women by cis straight men who express a deep insecurity coupled with thrill and desire. Can you speak more to this paradox?

AW: A line I encountered in my scholarly work on colonialism speaks directly to this dynamic: “Disgust always bears the imprint of desire.” There’s a sexual element in a lot of male-perpetrated violence that stems from the fear of being diminished, of having their manhood sucked out of them if they surrender to their desire for the feminine. And I think trans women activate this fear with particular intensity. We are women, and some trans women are beautiful in conventional cis terms. To the transphobic brain, though, it’s “Well, I’m sorry, you were born with male plumbing, so you’re not women.” And the thought that we’ve had bottom surgery makes us guilty of the sin of rejecting that God-given plumbing—makes us the castrated, feminized monsters that transphobic cis straight men fear the feminine other will make them. So, if a man like that encounters an attractive trans woman, this desire-rage dynamic can kick in, especially if the man didn’t initially clock her: “Oh my god, that’s a man, oh my god, I’m gay, oh my god, kill kill kill!” There is actually a gay panic and trans panic legal defense, though states are thankfully starting to ban it now.

SK: There is also a deeply sad self-doubt that haunts some of the women you write so poignantly of, as in the final lines of “Remembrance”: “the fear / That as the motherfuckers came at you / You might for a second have felt / I deserve this.” How does this reflect the erasure of trans folks throughout their lives?

AW: When I pitched the book, luke kurtis said that line was like a gut punch. The feelings of monstrosity born from dysphoria and internalized transphobia, which often become acute during the violence of puberty, and the suicidality, cutting, and other self-destructive behaviors those feelings prompt—this is how our self-erasure plays out. It’s a real question how you survive all that? I was pretty good at compartmentalizing and repressing—a lot aren’t, and don’t survive.

SK: It must be truly devastating.

AW: Absolutely. I think of internalized transphobia as a form of psychological colonialism. We are basically invaded by these voices telling us, no, you’re not who you think you are. We also face elevated levels of violence and harassment, but this psychological violence, this colonization of our identity, is typically as harmful, and for a lot of us, is more so. In “On Seeing England for the First Time,” Jamaica Kincaid writes about how she was thoroughly erased as a colonial subject raised in the British empire: because everything but the sea, sky, and air had a British stamp on it, she was reduced to “a hole filled with nothing.” I think that’s a great analogy for what we go through. When I was growing up, everybody modeled the gender that they told you you were. Everyone was policing you. You were swiftly and often severely corrected if you stepped out of line. If as a trans kid you saw yourself at all, say on television, it was as a joke. Things are a lot better now, but we’re still fighting in a lot of places for our existence to be recognized. Some states over the last year have outlawed medical care for trans kids under 18. The Texas GOP is now asserting that parents who help their children get gender-affirming care are guilty of child abuse and should lose custody. That’s what erasure looks like.

SK: You combat erasure with the bursting tongue, the originator of ideas shared, and wounds lovingly licked. Philomela’s tongue is even severed by her attackers, “cuz this is all u are.” The tongue must truly be powerful, the tool of any “truth stammering girl.”

AW: The importance of voice for trans folks is complex. We are forced to reckon with our voice, as with our body, in ways that cis people take for granted. If others perceive your voice as incongruent in cisnormative terms, if you don’t sound the way they think a woman or man should sound, your risk of being harassed–or worse–increases. That’s why simply being heard, being visible, is a political act. When we’re still fighting to be recognized as fully human, speaking or just walking down the street can be about claiming our place. It’s about saying and showing who we are: this is what it’s like to be us. That’s how understanding begins.

SK: And what about for yourself?

AW: For me, voice was part of the larger quest for congruence. I remember the day I became aware of how tense my arms were when I was out. I was doing qi gong at the counseling center, and the young trans guy who was leading it said something about relaxing my arms, and I realized in that moment how much I’d been reining myself in, clenching myself even. It was almost like I’d erected a wall at my shoulders to prevent myself from entering my own body. Once I broke through that, the fluidity came, and suddenly I’m in my arms, I feel they’re part of me, and the same with my legs, my walk—and my tongue, my voice, as well. That’s the first image in the poem “Love Song (Congruence)”: “the sweet / Snow-melt bubbling from this tongue.” After the freezing, the everything-clenched, it’s like the thaw, the spring, and I inhabit my body for the first time, and in embracing myself, I also find my voice. I feel free to speak my truth.

SK: The spring thaw—it’s almost like the fluidity of the sea.

Anastasia Walker is a poet, essayist, and scholar originally from Maine but now calls the Pittsburgh area home. She volunteers for the Transgender Law Center’s Prison Mail program and is a proud member of her community’s Indivisible group. She’s a passionate amateur photographer and musicologist and loves going for long walks and swimming in the ocean.

Sarah-Jean Krahn is an experimental feminist poet and author of A Girl Who Was His House (Gothic Funk Press, 2021).

Text copyright © Sarah-Jean Krahn and Anastasia Walker

Support independent and experimental work

If you like what we do, help keep it going:

🛍️ Make a purchase from our shop

📬 Join our newsletter for occasional updates

✉️ Get in touch if you have questions, comments, ideas, or pitches