Dudgrick Bevins on teaching, trauma, and telling stories 🧑🏫😨🖋️

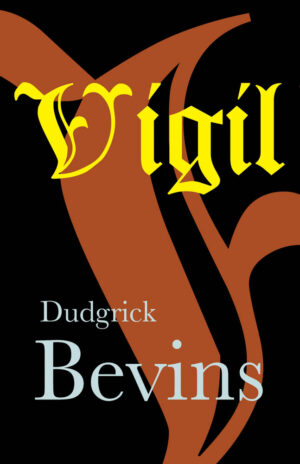

In the sweaty New York City July heat, I sat down with my friend and colleague, Dudgrick Bevins. We talked about his new poetry volume, Vigil, exploring a new generation’s relationship with school shootings and the unheard voices breathing desperately into a chorus of narrative poetry. Bevins is not only a prolific interdisciplinary artist and poet but a fellow educator. Here he reflects on what it means to navigate the role of teacher when talking to students about gun violence while still processing the chaotic internal emotions that each individual experiences in the aftermath of traumatic school shootings.

AG: What inspired you to write Vigil?

DB: Well, in some ways, you were there at the genesis of the project. The Parkland School shooting had just occurred, and we were watching the news about it every morning. Then we were asked to teach a lesson on it. The students were saying the same things to me that I wanted or tried to say to my teachers after the Columbine shooting when I was in seventh grade. But even now, as an adult, as a teacher, I didn’t have the answers. I spoke with you about it after, and you said you had a great conversation, that it was unstructured, authentic, respectful. But it was such a struggle for me, and I didn’t know how to lead a discussion about something as traumatic as school shootings. My default language is poetry, so that’s where I went.

AG: I remember it well. When you shared an early draft with me, you still hadn’t quite figured it out, though.

DB: Yeah, you said, ”Dudgrick, this is unfinished.” You were right; the first manuscript left me out. But you helped me see that I’m part of the equation, too. So, the voice of the teacher in Vigil only exists because of that. You helped me find my voice!

AG: Do you think Generation X has a similar or different relationship with school shootings than millennials?

DB: By the time Columbine happened, Gen X was mostly out of school. I think y’all saw it coming; if you look back at films like Heathers and Pump Up the Volume, it’s easy to see the angst that was building. Millennials—my generation—we came up with every institution around us collapsing before we could get anything out of it: dot-com, housing market, the shadow of AIDS, Unabomber, Oklahoma City bombing, Waco. With Clinton’s infidelity and Lorena Bobbit’s amputation, even the body wasn’t stable. Columbine was horrific, but it was also just another sign that nothing could be trusted. I say this as an early millennial with some strong Gen X views. Our students, Gen Z, have more fight in them than my generation. X lost hope. Millennials never had hope, but their tendency to be more politically progressive and philanthropically minded hints that maybe some shred of hope still exists.

AG: What do you think those particular students who you taught about Parkland would think of the poems in Vigil?

DB: The connection between school shootings and police brutality, that is, the misuse of authority and the bullying of individuals, is not lost on them. When I look at young people and the way they are fighting now, the walkouts that followed the Parkland shooting, the protests about gun reform, the acceptance of queer sexuality and nonbinary gender expressions, and support of Black Lives Matter, I see a new generation making the kind of ”good trouble” John Lewis spoke about. The queer kids, especially, are barreling forward with the passion of a fiery Larry Kramer speech. I feel like positive change is inevitable. And I hope Vigil can be part of that.

AG: Or at least invoke some personal inspiration that motivates action or ”good trouble.” Another aspect of Vigil that I picked up on was the notion of being seen and not seen. Whether it is the aftermath of a memorial at a football stadium, teenagers’ relationship with social media, or the shooters asserting their presence as killers in hallways, it all plays with the theatrics of having an audience or not.

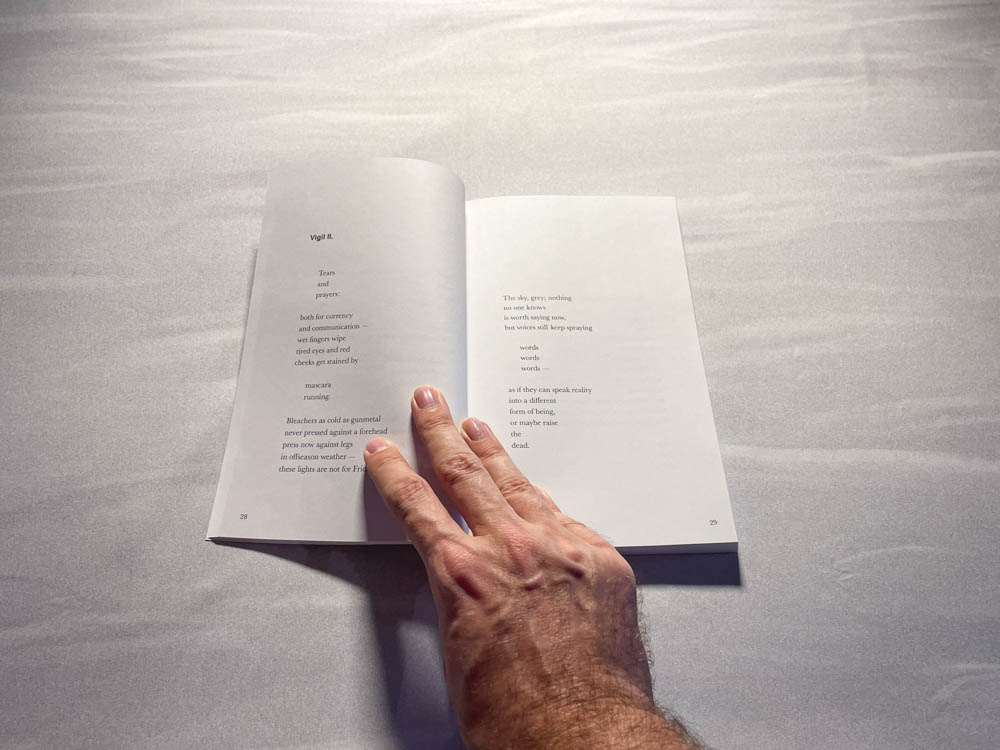

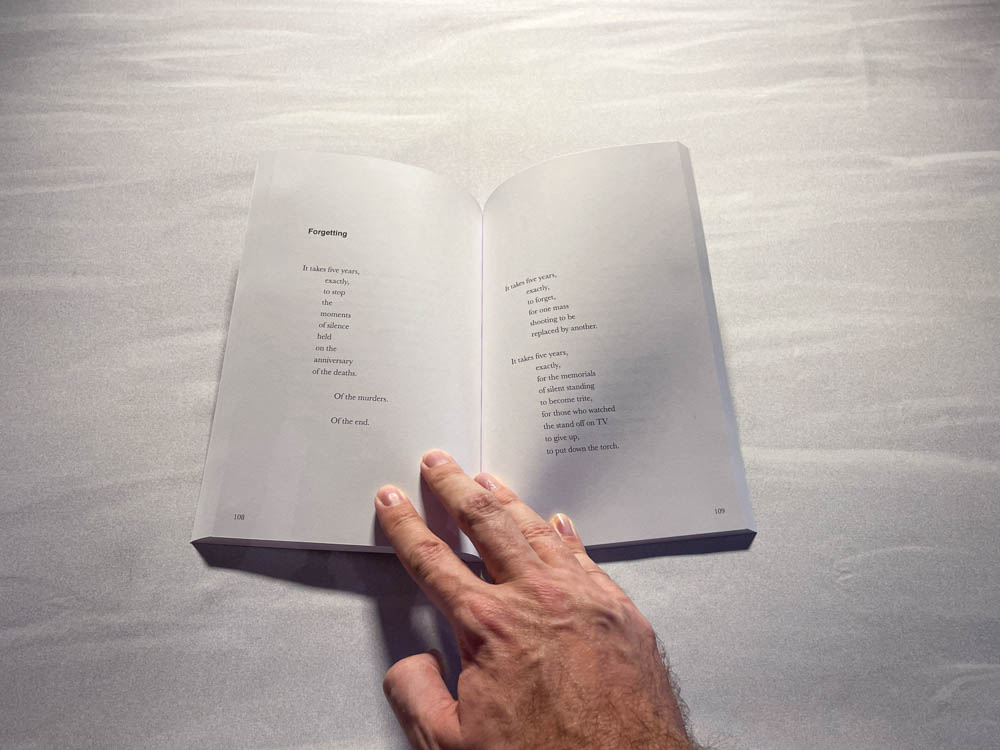

DB: Absolutely. Visibility versus invisibility is a central theme, not just in terms of being and feeling seen but also in terms of feeling heard and being able to speak. In the book, the dead have a lot of animosity towards themselves and others for what was said and what wasn’t. I hope my characters are human in their imperfections and not totally unlikeable, but I also hope there is a cringe factor about who said what, who didn’t, and why. My characters fail to say the right things to the right people. In the aftermath of any major crisis, we try to make the victims visible. In a fictionalized setting, I can make them not only visible but culpable for what they said or didn’t.

AG: Vigil deals with the aftermath more than the event. How did you navigate imagining the internal feelings of each person named as titles to your poems?

DB: I came up with 26 different characters, one for each letter of the alphabet. It was difficult figuring them all out. I wound up thinking about cliques and archetypes. It works because that’s how high school works. I knew I needed a group of jocks, competing overachievers, drama kids, religious zealots, and politically inclined kids. Then I thought about what each might say and hide, what they might admit and what they might deny even after death. I wanted it to be like Spoon River Anthology by Edgar Lee Masters. And just like when I read Masters’s work, writing Vigil required a lot of going back to what was already said. Depth is revealed as each character talks about the others. Ultimately, the 26 voices come together in a conclusion that sings like Whitman—that’s the 27th voice.

AG: And that’s you, the teacher?

DB: I wouldn’t say it’s me. I mean, there’s part of me in that character. But there’s part of me in every character I write.

If you or anyone you know struggles to talk to children about school shootings, please see advice from the American Psychological Association or call one of its crisis hotlines.

Dudgrick Bevins is an interdisciplinary artist from the North Georgia mountains. He studied English Education, American Studies, and Gender Studies before taking the underground queer railroad north to New York City. He lives with his partner, a fellow artist and writer, and a small woodland spirit named Hada. He teaches a variety of high school seminar courses and creative writing.

Adam Garnett is a poet, educator, and freethinker from Boston, Massachusetts. He currently teaches interdisciplinary art courses in Harlem, NY.

Text copyright © Adam Garnett and Dudgrick Bevins

Support independent and experimental work

If you like what we do, help keep it going:

🛍️ Make a purchase from our shop

📬 Join our newsletter for occasional updates

✉️ Get in touch if you have questions, comments, ideas, or pitches