Dudgrick Bevins on fear, family, and finding his spirit animal 😱👨👩👦🦌

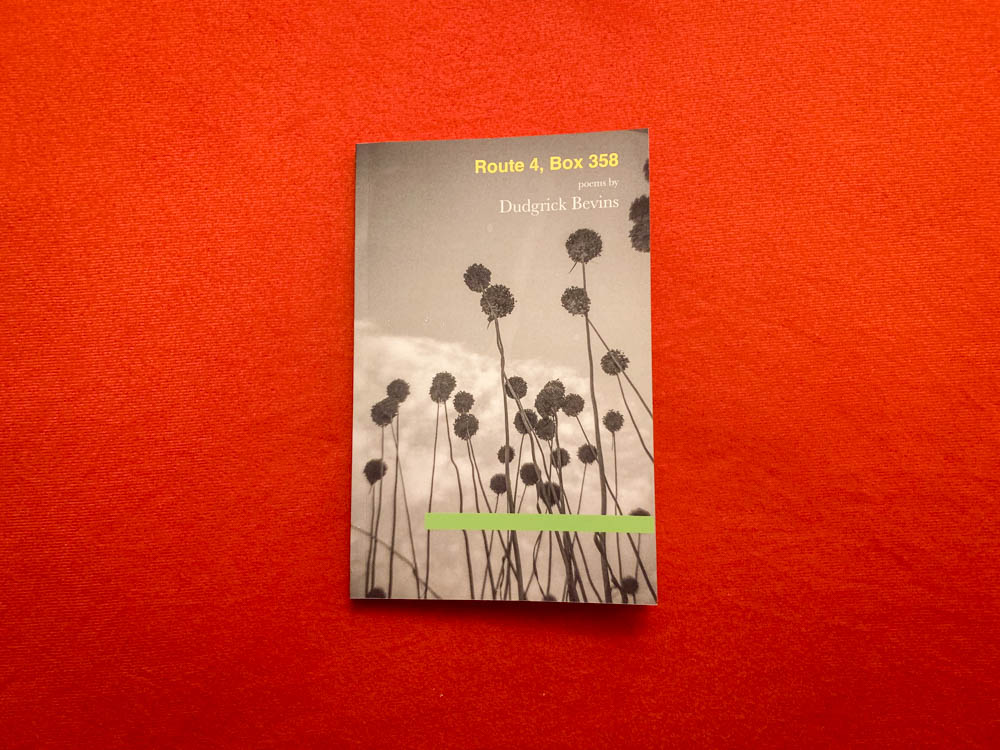

I sat down with Dudgrick Bevins to discuss his debut full-length poetry collection, Route 4, Box 358. Struck by the way he explored his relationship with home, family and—ultimately—himself, I wanted to understand the stories behind the stories and what motivated Bevins to reveal the stories he did.

AG: What was your main inspiration behind these poems?

DB: The book collects three years of writing on my upbringing and home, so to say there is one inspiration or even a main one would be a lie. But, I can say that I didn’t start writing about Georgia until I had been away from there for two years. I needed distance, space, time. I couldn’t see where I was from when I was still living there. So, maybe I could say living in New York is my main inspiration for writing about my life in Ellijay, Georgia.

AG: Why do you think that is?

DB: When I lived in the south I felt like it wasn’t my home, it wasn’t part of me; I didn’t see myself as southern. But after moving to the city I started to notice some of my deeply Southern habits, from there I started reflecting on that southern part of myself and why it was so clear here and so invisible there.

AG: What are these deeply Southern habits you mention?

DB: Little things like eye contact with strangers and waving at people who smile. It’s small things, but I can tell it sets me apart at work when I have to smile at the same coworker every time I pass them in the hall.

AG: This is a deeply personal work. What were some of the challenges in writing it?

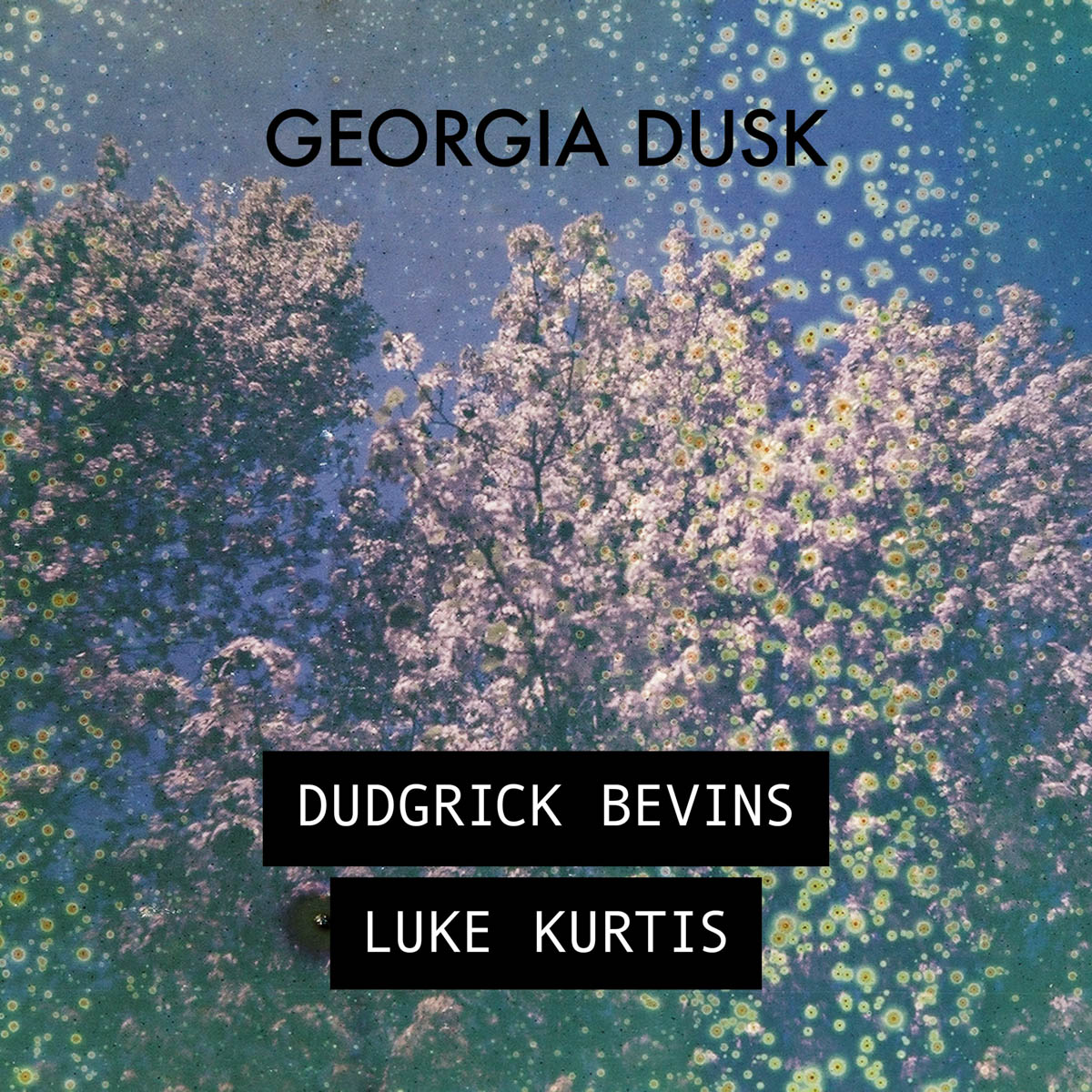

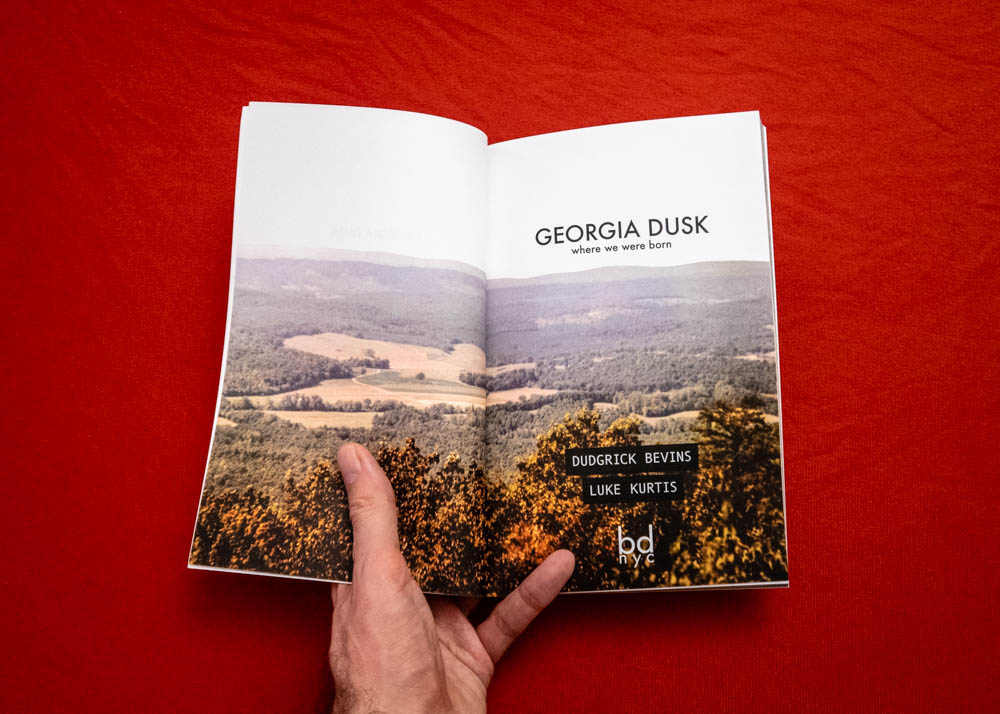

DB: luke kurtis and I wrote a book together called Georgia Dusk which explored some of the same themes, namely, me looking back on my time in Georgia. In it, I wrote about a time I got lost in the woods and another time I almost hung myself, accidentally, from my swing set. I wrote about being saved by my parents in these instances: my father coming to my cries from the edge of the woods, my mother racing down to untangle me from the swing set. These were moments I found my parents heroic, but when they read that book they didn’t feel heroic. My mother, in particular, felt slighted because I wrote something along the lines of, “she saved me for the last time.”

AG: Why do you think that bothered her so much?

DB: I’m not her, and I’m not a parent, so I can’t really see the offense there, but there was some taken. After that, I felt an odd mix of remorse that I had upset her and frustration that she didn’t understand what I wrote. I say all this to say, the challenge I face writing about real people and real events is a problem of fear: fear of upsetting my family, fear of misrepresenting them, fear of exposing them. There’s a lot of fear around hurting them.

AG: But not enough fear to stop you?

DB: Apparently not.

AG: Has your family read it?

DB: With this book, Route 4 Box 358, I sent them a copy as a gift to pre-read it. I was prepared to make alterations if they found inaccuracies or really hated something I wrote; I only did this because it was about them. My other writings, well, they can take them or leave them, but this was about them in big ways. I felt like they deserved input. Unfortunately, my father got diagnosed with cancer shortly after I sent them the book and they didn’t get to finish it before it was released. Aside from my parents, no one else has read it. I’m sure I’ll end up giving my grandmother a copy, but I don’t really talk to anyone else in my family, which I think is reflected in the fact that I don’t talk about them in the book.

AG: I’m curious—you incorporate quite a bit of wildlife into your writing. What would be your spirit animal?

DB: It’s funny you ask about my spirit animal. I recently went on a retreat and I had to identify a spirit animal. It changed throughout the retreat, but I settled on a stag. I think the stag projects what I want to be: independent, proud, peaceful but ready to fight, something that challenges order but also finds a place within it. This is all in my head though; I mean, that’s where spirit animals live.

AG: Did animals play a role in your childhood?

DB: Yes. I also think that the stag resonates with me because I used to work at a wild animal sanctuary where we took in bears, cougars, deer, foxes, raccoons, you name it. If it was injured or orphaned we would take it in. I loved all the little furry things but I hated working with the baby deer because when I would bottle feed them they would shit all over me—it was so annoying. At one point we had a doe that grew to full size and became attached to the sanctuary; she wouldn’t leave when we tried to release her and ended up acting like the sanctuary’s pet dog. People would coo over her, pet her, and when she wasn’t getting the attention she wanted she would start head-butting people. It was cute and annoying. She disappeared one day; we suspect a neighbor to the sanctuary shot her.

AG: But what about the stag?

DB: I never got to see that full life cycle with a male deer, a stag, so maybe that is why I focus on them now. That and it is kind of karmic, right? The animal that used to annoy me is now my spirit animal. The stag means so much to me, there is even a poem about one in the book. I’ve got a stag head tattooed on my leg. Images of the deer cover my walls at home. And animals are such a big part of southern life—I grew up seeing deer and bears along the dirt roads at night which my parents would stop and stare at with deep reverence; people hunted, not my family, but people hunted and you’d see heads on walls—it’s strange, I think in the south they both honor wildlife and take it for granted because they see it so much, but we didn’t.

AG: The Ku Klux Klan has a presence throughout this work and seems to highlight your feelings of alienation.

DB: Yes, as I write in the introduction, the Klan was a given in my hometown. I didn’t fully realize it as a child; it was invisible to me. But at the same time that I started to recognize my own difference, my own queerness, I started to see the presence of the Klan. I kind of came of age with as they were making their last gasps in Ellijay, but at the time their presences felt big and imposing. I couldn’t tell that the rallies they had on the courthouse steps were going to become fewer and farther between. I didn’t realize that their Northeast headquarters was going to close or move.

AG: Yes, but how did that shaped who you are today?

DB: Sorry, I got lost in my memory for a moment. It was my sixth-grade year that the Klan had the first rally I can remember. That was the same year I came out to myself as gay. As they stood on the courthouse steps and shouted about the gay agenda and the problem of immigration I was realizing that there were people out there that would hate me just for existing. I remember driving by the rally with my parents to get a glimpse of the spectacle because let’s face it, hate is always a spectacle—you can’t look away; just think of the current administration. Anyways, not long after the rally, two gay-owned businesses were vandalized; well, one was vandalized and the other got burnt to the ground. You asked about a feeling of alienation: yes, it makes you feel alienated to be part of a group others think are a problem, especially one that needs to be met with that kind of violence.

AG: In ”Mercy Killing,” your grandmother told you, ”sometimes you have to kill things to save them.” Do you believe this?

DB: Yes, I think.

AG: That’s all you have to say about that?

DB: Let me tell you another story that isn’t in the book. Once we had a hamster who escaped his cage and got stuck on one of those terrible glue mouse traps. My mother and I spent hours trying to pry the little guy off with a butter knife, but as soon as we would get one sticky bit free another part would get stuck. It was terrible, funny, horrifying. I remember we were laughing and crying at the same time. It hurt to see Stempy, the hamster, suffering but there was also an absurd humor in our efforts. Eventually, my father came home, he tried too to free Stempy, but with the same success—that is none. My parents decided that the best thing to do was kill him, to “put him out of his misery.” My father took him outside and shot him. A dramatic ending for such a little helpless creature. We all cried.

AG: Yes, but do you believe that was the right thing to do?

DB: I believe it was the best we knew how to do, and sometimes, that is the same thing as the right thing to do. I know now that vegetable oil could have saved my hamster’s life, but some decisions must be made without the benefit of the internet.

AG: What do you want people to walk away with from this work?

DB: I want people to know two things: One, no thing, no place, no person, nothing, is simply one thing or one way. I grew up somewhere beautiful—mountains, streams, wildlife—I grew up surrounded by people that loved me but I also grew up in a town where the KKK held their rallies and likely destroyed local businesses. My hometown is both a woodland sanctuary and a haven for bigotry. Two, we can’t escape what we come from. I wanted away from the south for so long, I wanted to see and be somewhere different; now that I am I see myself as more southern and more connected to the place I came from. The beauty and the ugliness are inside of me; I carry them with me.

AG: Who is your primary audience?

DB: When I imagine people reading the book I imagine three groups: One, and most personally, my parents. It is important to me that they have a record of my feelings on growing up, especially of the beautiful moments. Two, expatriates of the south, those souls who like me took the risk and went to the “somewhere else” they always felt drawn to. Those are the people who the book is really for. And three, people who still live in my hometown; they might be the people who need to read the book the most because when you are in a place it is hard to see all sides of it; my hope is that my view from a distance might give them the same opportunity, and therefore the opportunity to continue to change the place for the better.

Dudgrick Bevins is an interdisciplinary artist from the North Georgia mountains. He studied English Education, American Studies, and Gender Studies before taking the underground queer railroad north to New York City. He lives with his partner, a fellow artist and writer, and their very grumpy hedgehog, Ezri. He teaches a variety of high school seminar courses and creative writing.

Adam Garnett is a poet, educator, and freethinker from Boston, Massachusetts. He currently teaches interdisciplinary art courses in Harlem, NY.

Text copyright © Adam Garnett and Dudgrick Bevins

Support independent and experimental work

If you like what we do, help keep it going:

🛍️ Make a purchase from our shop

📬 Join our newsletter for occasional updates

✉️ Get in touch if you have questions, comments, ideas, or pitches