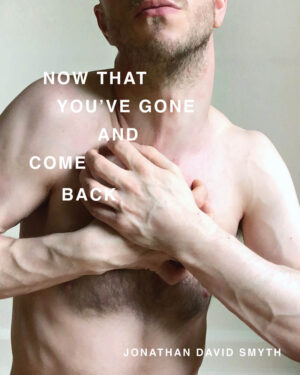

Michael Harren on animals, grief, and his multimedia marvels 🐓😭🎹

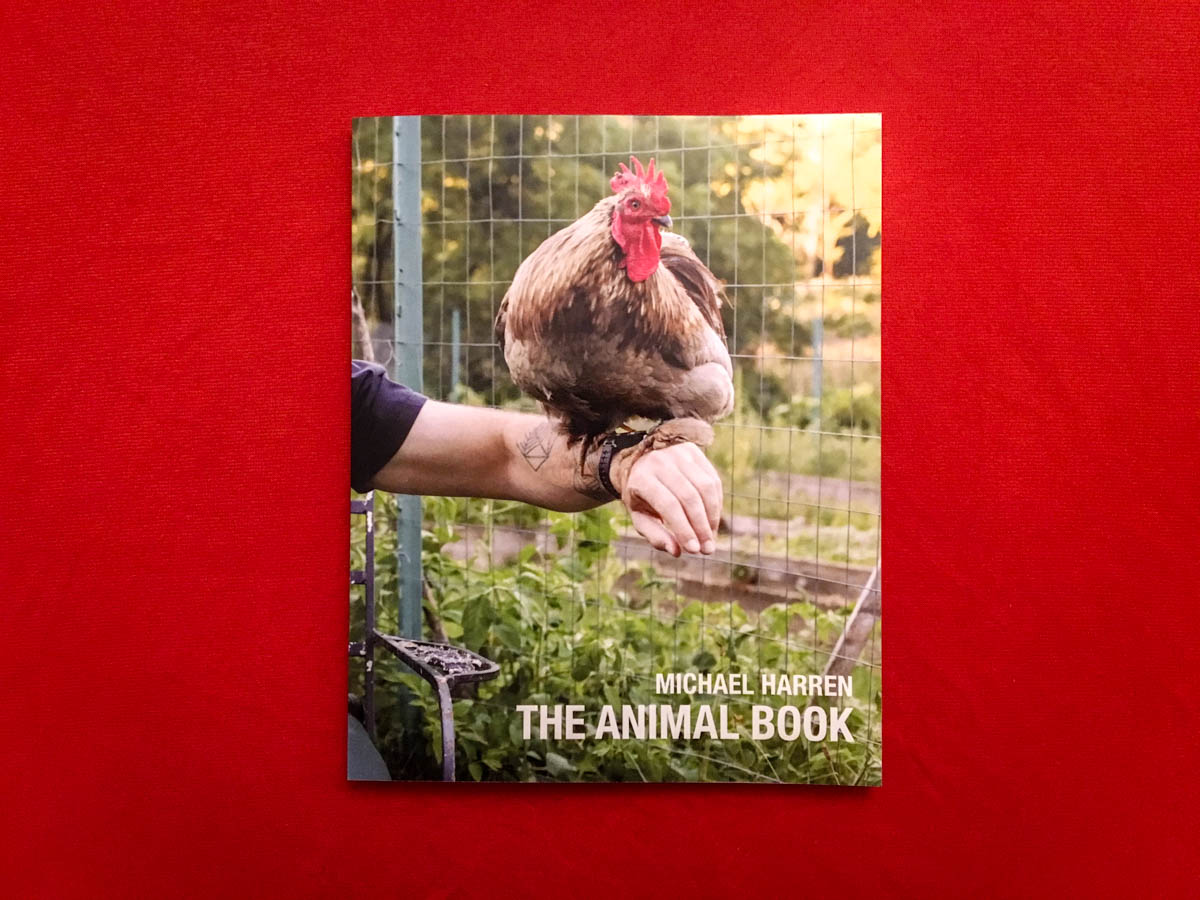

Both of our bellies full of watermelon, I sat down with Michael Harren to talk about The Animal Book, the book that archives The Animal Show, which in turn archives Michael’s multimedia artistic stylings, animal activism, and the culmination of the two: his vibrant, evoking artivism. I was eager to hear about the melding of such diverse methods, but also what lies behind them—the man, the emotion, the existential uncertainty. Michael shared his grief and joys with me in a humorous, self-effacing way.

SJK: Can you tell me about what artivism means to you and how it’s been effective for you as an artist?

MH: Artivism is simple. It’s a combination between art and activism: creating something with the intention of sharing an activist message. It’s been most effective in ways I never expected. One example is when I was recording The Animal Album. I recorded it at a studio in my neighborhood, so I knew the guy. I was talking about rescuing chickens, and it didn’t dawn on me till later when I was walking down the street and he came riding by on his bike and was like, ”Hey, Michael! Man, those stories really stuck with me.” So, I wasn’t doing activism, I was recording my album, and that conveyed a message.

SJK: You were the ”artivist in the room.”

MH: Yeah, exactly. Artivism makes the message more accessible. When you decide to go see a show, you’re opening yourself up to hear a message, someone’s story. You’re open to hearing things you might not be if you see it on a Facebook thread or hear it in conversation. People can be defensive, but defenses are down when they’re consuming art. That sounds a little bad, like I’ll get them when they’re defenseless. (laughs). It’s just the way I communicate!

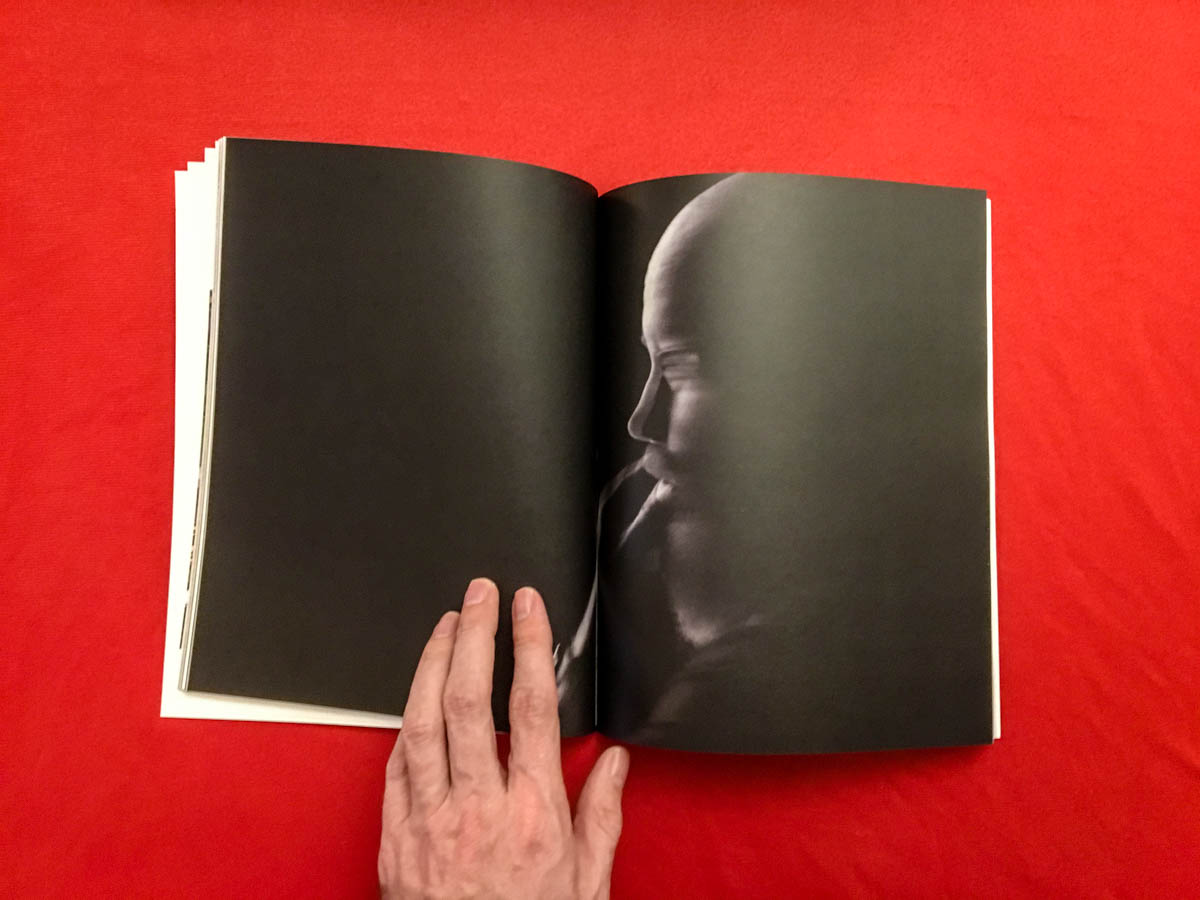

SJK: You work in multimedia, and you even document your own documentation—like the photos of you with the camera in The Animal Book. What is the value of archiving the artistic process itself?

MH: Documenting myself documenting is multiple layers of things. It’s more immersive for me as the artist and for the audience. It opens up the connection between them. I have a Patreon page, and one of the things that’s exciting about it is also a little frustrating. It’s so hard to get people to engage there, but when they do, it’s really interesting to share between the artist and the audience. When I was in high school and I would go to the record store, buy an album, and listen to it at home on headphones, that was it. There was no ”what are they doing on Twitter,” ”what’s their website like,” so it was a big distance between artist and audience. Sharing more of the process, the world surrounding the artist, and the creating of the art makes the connection stronger and deeper.

SJK: In The Animal Book you also inventory horrific animal abuses, yet intersperse them with photographs of musicians on stage. I would be reading something really difficult and then I turned the page and it’s a picture of the cellist. Is music one of the only responses that can fully capture the suffering you’ve borne witness to?

MH: I don’t even know that I could capture the animals’ suffering; I think it’s really capturing how I feel about it.

SJK: What would be an example?

MH: In ”Their Eyes,” I went to a vigil at a slaughterhouse in Los Angeles where truck after truck was packed with pigs—like packed. There was a woman there who does Facebook live documentation of these things, and I remember her asking me what it was like to be there for the first time. I couldn’t put it into words. I still can’t put it into words.

SJK: That must be why you put it into music—it brings out your anguish.

MH: And the video that I made to go with the music. All of that together captures it. I’d been vegan for close to ten years when I went to this vigil, and even then, I still didn’t really think about animals as individuals. I knew bacon came from pigs, but I didn’t know it came from an individual. Seeing those trucks and looking through those holes and seeing the expression on their faces was devastating. And it’s like, who am I to be devastated with it? But it is, it’s extremely sad to see—heartbreaking.

SJK: You really have a way with using music and visuals to get your ideas across.

MH: I think that that’s why music and different non-verbal forms of work exist: it’s a way to communicate things that there just aren’t words for, when maybe it’s just too…emotional; it’s too much. Maybe that’s why I’m stuck trying to describe it now, too. When you communicate with music you don’t have to try to be specific because it’s sound that’s doing it. It’s emotion itself, in a way.

SJK: In both Tentative Armor and The Animal Book, grief is prominent. How would you compare the grief experienced through each?

MH: Tentative Armor was the first time in my life that I really allowed myself to be gutted by something. For a long time I was walled off, so that’s what Tentative Armor is about. It’s about trying to stay safe emotionally while looking for ways to beat my demons, sexually. Meanwhile, my mom’s death served as a transition in my own life; it was such a big loss that I couldn’t keep the walls up. For years I wanted to write a story-telling piece; I always had this desire to combine music and stories, and that grief part of me said, ”Hey, run with it while the walls are down, let this go, let it happen.” That was my first experience with feeling something so strongly that I couldn’t hold it back.

SJK: That reminds me of my favorite song of yours, ”Go” from Tentative Armor. How did the flood of emotions help you move forward?

MH: It opened me up to feeling grief and compassion for others. I was already vegan when my mom died, but those feelings are connected because they’re both about loss. The Tentative Armor grief is about my own loss, and The Animal Show is about witnessing someone else’s and trying to understand why. The majority of people get mad at veganism, and that was a challenge for me. But I’ve had black-and-white thinking about animals, too. I was vegetarian and an animal rights activist in my twenties. But then I just turned it off. So, the grief from The Animal Show is also the sadness that a lot of people just don’t really care about animals or feel they can’t.

SJK: I was really struck by the part of The Animal Book centered on your conversation with the Disembodied Voice of Heaven (DVOH). It felt like you were trying to call on the audience to face their responsibility by simply sharing your own story.

MH: It’s interesting, my director for The Animal Show at the time wasn’t even a vegetarian or at all interested in animal rights, but he was saying, ”I see your Facebook posts after you come from a protest or from witnessing some of these things, and I know you’re pissed off. You’re not saying that in the show. You haven’t written that yet.” It was really interesting having him say, ”You need to be angrier,” so that’s where this section came from.

SJK: Interesting that the anger culminated in a personal confession.

MH: Yes, that whole spoken word piece is about my history. People push back about their role in what’s happening to animals, like: ”Oh, here comes a holier-than-thou vegan.” But I wanted to really share that no, I’m not anything special, in fact here’s how fucked up I am. And in fact, that fucked-upness is what made me decide I needed to be kinder to everyone, including animals. That part of the story is really about my belief that we’re all interconnected as different types of humans and different species.

SJK: At one point you mention our oneness. So, there’s an element of the spiritual in your work alongside some existential uncertainty, like when you say, ”Or maybe I’m just dust.” How does the spiritual fit into your life and your artivism?

MH: (laughs) I think that’s ever-evolving. Spirituality has been a really fluid thing for me. But the thing that stays constant is the idea that in a lot of ways it’s so simple, just: we’re all connected. Do unto others; that simple stuff.

SJK: So, your spiritual side relates to the concept of responsibility?

MH: Maybe! I just interviewed Britt East for my podcast, MikeyPod, who wrote a book called A Gay Man’s Guide to Life. The thing that I took from the book was something that I forgot, which is taking care of your body so that you can support your community. During quarantine I’ve been full-on hermit, not eating well, watching a lot of tv, gaining weight, not taking care of myself enough, and I’ve been in this guilt cycle that it was all self-centered reasons to take care of myself. It was helpful in my conversation with him to realize that I’m supposed to do that stuff so I can show up outside my apartment and do my job of helping lift up the people and beings around me. That’s a roundabout way to talk about what I believe spiritually, but our responsibility to each other is what I was trying to fold into the show, too.

SJK: In The Animal Book you talk about feeling defective. How have your experiences as a gay man helped you relate to animals on that interconnected level?

MH: Yeah, that’s so funny, that’s a connection that I didn’t even notice was there, so that’s cool. Part of what makes me open to what animals experience is that I felt like I was defective and, as a kid, I sort of liked that idea. But, I wanted to be defective in ways that I wasn’t already. I was embarrassed by the ways I actually was different, like being sensitive and creative. Later, realizing I was gay made me feel like an outsider. Coming to terms with that led to a quest for fairness that made me more sensitive to animals and gave me greater empathy for those who are treated less than because they are different.

SJK: Can you share an animal story that didn’t make it into the book?

MH: One of the things I loved when I was on tour was feeding time at a sanctuary that was home to thousands of chickens rescued from being ”culled” (gassed) when they were no longer producing eggs. I spent my mornings cleaning the barns. It was intense farm work in the heat. Still, caring for these thousands of chickens was a soul-lifting experience, and maybe a little karmic payback for all the years I consumed eggs. But they also brought me so much joy.

SJK: Joy! Thanks, Michael. We could all use a little bit more joy these days.

Michael Harren is a Brooklyn-based composer, performer, educator, and activist who combines elements of classical composition with experimental electronics and storytelling to create hypnotic, boldly intimate works, reminiscent of Laurie Anderson, Peter Gabriel, and Dead Can Dance.

Sarah-Jean Krahn is an experimental poet and author of A Girl Who Was His House (Gothic Funk Press, 2021). She is going on her twelfth vegaversary.

Text copyright © Sarah-Jean Krahn and Michael Harren

Support independent and experimental work

If you like what we do, help keep it going:

🛍️ Make a purchase from our shop

📬 Join our newsletter for occasional updates

✉️ Get in touch if you have questions, comments, ideas, or pitches